Search Engines As A Persuasive Technology

Captology is an important idea in exploring and understanding how search engines work and how they will evolve. By definition, Captology is the investigation of how various aspects of interactive computing products can be used to influence attitudes or behaviors. BJ Fogg, a Stanford researcher, coined the term Captology from the acronym “CAPT,” or Computers as Persuasive Technologies, in 1996.

There are numerous studies that focus on exploring how digital devices persuade us — like computers, phones, apps, and video games, but what I want to highlight is how search engine uses different persuasive forces to guide and assist our day-to-day decision-making processes.

Search Engine in your life

Instead of consulting an encyclopedia, you ask your question on a search engine. You order the favorite book your mother wanted online rather than searching local bookstores. The convenience and time-saving benefits of using search engines persuaded you to change your behavior with clear intent. Real persuasion implies an intent to change attitudes or behaviors. This means that persuasion requires intentionality and therefore not all behavior or attitude change is the result of persuasion, it must be associated with clear intention.

A rain, for example, may cause people to purchase umbrellas, but the rain is not a persuasive event because it is not associated with any intention. (However, if an umbrella manufacturer is capable of causing rain, then the rainstorm may qualify as a persuasive tactic.) A search engine qualifies as a persuasive technology only when those who create, distribute, or adopt the technology do so with an intent to change attitudes or behaviors.

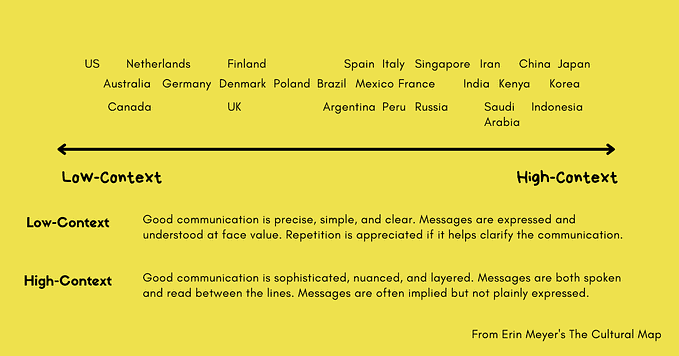

Robert Cialdini, an experimental social psychologist, and a compliance professional cited eight (8) principles of persuasive psychology. These are the principles of reciprocation, liking, social proof, authority, scarcity, commitment and consistency, and unity. In his book, he emphasized how these invisible forces play an important role to produce a distinct kind of automatic, mindless compliance from searchers and willingness to click without thinking first.

Liking

We are more likely to be persuaded by people we like. Cialdini emphasized 5 elements behind the principle of liking and one of them is similarity. Liking is based on sharing something similar.

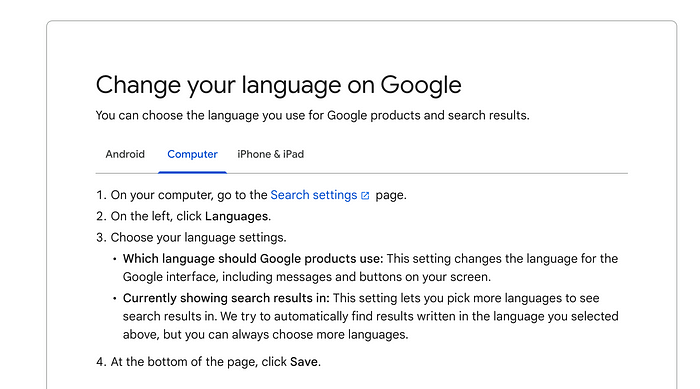

If you are adding your correct language to your browser settings, most probably search engines will be speaking your language.

Scarcity

Scarcity is the perception that products are more attractive when their availability is limited. People are more likely to want something rare if it is offered to them.

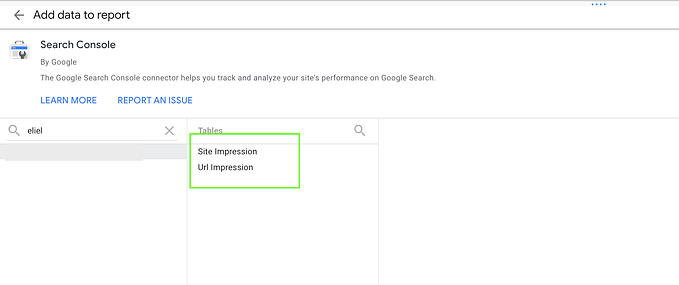

In paid shopping results, also known as Product Listing Ads (PLAs), Google shows to sell products directly to customers using rich information such as images, and pricing.

Commitment and Consistency

Consistency is activated by looking for and requesting small initial commitments. This principle asserts that humans have a strong desire to be perceived as consistent. As a result, once we’ve publicly committed to something or someone, we’re far more likely to follow through on that commitment.

When Google wants to find an answer to a question that isn’t in the core Knowledge Graph, it may look in the index. This generates a unique type of organic result based on their commitment to providing information extracted from different sources. The example query shows different organic results we have People Also Asked, Recipe Pack, and video.

Authority

This is related to our tendency to be persuaded by authority figures, people, objects, or anything who demonstrates knowledge, confidence, credibility on the subject, or proof of existence.

For queries with local intent, the SERP will frequently include a Local Pack containing the three physical locations Google considers most relevant to the keyword.

Knowledge Panels (aka Knowledge Graph) extract semantic data from a variety of sources such as Wikipedia. For a desktop search, they typically appear to the right of the organic results.

Social Proof

The more people who agree on an idea, the more likely it is to be correct. Most of the time, we use the actions of others to decide, especially when we see those others as similar to ourselves. If a particular restaurant is always full of people, we’re likelier to give that establishment a try.

For products, recipes, and other relevant items, review stars and rating data are sometimes displayed.

Summary

Search engines persuade us in innumerable ways. Easy access to our queries changed our attitudes and behaviors. When you first visit a search engine results, it will show you links based on the popular results. If it detects that you have previously visited something on the site or elsewhere on the internet, it will use that information to refine the results.

There is a popular belief that as search results become more personalized, the chances of serendipitous findings — finding something you like that you were not looking for decreases because the SERP will be populated by paid campaigns, and competition for organic searches increases.

Search algorithms are getting more powerful and persuasive. They start making predictions that go beyond the obvious. By examining these different ideas of persuasion, we have a glimpse of what search engines are trying to do to become a persuasive technology and serve their purpose to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful.

Is it the intention of those who create, distribute, or adopt technology to change users’ attitudes or behaviors? Do you think search engines are persuasive technology?